Climate Vs.

Your monthly guide to the big picture, the tiny details... and the bits in between! Climate Vs. takes the legwork out of trying to make planet-friendly choices.

As a Something Club member you’ll receive a monthly guide to understanding and shrinking the environmental impact of one very specific and very practical area of daily life.

Each issue of Climate Vs. is a plunge into something most people commonly use or do – such as wearing jeans, caring for pets, using the internet, making a sandwich or travelling for work. Finding trustworthy information, wrangling with statistics, untangling complex issues – it’s impossible to find the time, and hard to see how our individual choices affect the big picture. We’ve created Climate Vs. to help you decide where best to spend your time and energy – it’s a straightforward, practical guide to support you in taking achievable action in your own life.

But when Climate Vs. lands in your inbox each month, it’s just the start of the conversation. Head to the friendly Community Space to chat with others, ask questions, and share resources, ideas, recipes, and much, much more. Choose from The Something Club’s monthly programme of live events to help you build skills and confidence to put the things you’re learning into action and inspire others. Come along to the weekly Coffee Club, join the Book Club, or kickstart a Something Club campaign on an issue that matters to you – there are lots of ways to get involved.

To help you decide whether Climate Vs. would be helpful to you, here’s a sample edition concerning one of the greatest inventions of all time… lovely, lovely bread.

Oh crumbs! It’s…

In the immortal words of Mark Corrigan:

“Brown for first course, white for pudding. Brown's savoury, white's the treat."

So that’s sorted. But what should we look for in a planet-friendly loaf? Is it better to bake or buy?

Grab some toast and let’s take a look together.

give me the short version

Bread is a low carbon food, with thick sliced brown bread in a plastic bag producing the lowest carbon emissions.

The most significant thing we can do to reduce the footprint of the bread we eat is to use up every last bit – if every home stopped throwing away bread the UK this would have the same impact annually on climate change as planting 5.3 million trees.

So first, let’s make sure we agree on what we mean when we say ‘bread’. Because when it comes to bread-ish baked items, there’s a huge difference between a naan, a crumpet (lord of all bready things if you ask me), and even between different kinds of loaf.

To keep things simple, let’s look at an uncontroversial 800g loaf of 50/50 Kingsmill (so half white, half wholemeal). What’s the impact of this kind of loaf?

Starting with its carbon footprint, getting a single loaf from the soil to the shop shelf produces roughly 1kg of CO2e (see yellow box) – that’s about the same footprint as a paperback book or a hot bath. Or – thinking in terms of the energy that loaf provides us – it produces 0.53g of CO2e for every calorie.

For context:

🥔 potatoes produce 0.26g CO2e per calorie to produce

🧀 cheese is around 2.82g

✈️ asparagus air freighted from Peru generates 93g for every calorie. Woof.

What is CO2e?

Not all planet warming gasses are created equal and some – such as methane – have greater ‘global warming potential’ than others.

CO2e refers to Carbon Dioxide Equivalent and it’s a standard unit for measuring carbon footprints. It translates each different gas into the amount of CO2 that would cause the same amount of warming, enabling researchers to bundle all the warming gases up into a single number and making it possible to compare the footprints of different things.

Right now the average person in the UK has a CO2e footprint of 11.7 tonnes – this needs to shrink to 1.5 tonnes person by 2050 to try and limit warming to 2C.

Where is this carbon coming from?

The researchers who carried out the most recent and comprehensive study of bread’s footprint were surprised to discover that the bulk of that 1kg of CO2e – 62% – comes from the process of farming the wheat, with a whole 40% arising from the use of ammonium nitrate fertiliser. Making these fertilisers is a very energy intensive process, and once they’ve been applied to the soil they release nitrous oxide, a warming gas far more potent than carbon dioxide.

The next largest chunk of emissions comes from baking (28%) followed by transport (6%) and milling (4%). The plastic bread bag’s contribution to its climate footprint is negligible (and does contribute to keeping the load fresh for longer).

Once we get our loaf home, storage and toasting contributes additional emissions – toasting bread increases its footprint by about 25%.

We also chuck away 24 million slices (that’s about a million loaves, or 900,000 tonnes) every day.

Bread is the second most wasted food in the UK (potatoes hold the crown for ‘most binned’); as I write this, sitting at my kitchen table next to two sad plates of crusts my kids have abandoned (despite claiming to be SO HUNGRY), I can see how this happens, even when our intentions are good.

Around 23% of bread waste happens in our homes – to put this in perspective, this means we’re using 205,000 hectares of farm land unnecessarily, and emitting so much CO2 (318,000 tonnes annually) that we’d need to plant 5.3 million trees to offset it.

However, us consumers are only part of the picture as the bulk of the waste happens during production and transport, with – apparently – just 1% getting wasted at the supermarket (although this number comes from Tesco so let’s take it with a pinch of salt.) This 1% is largely as a result of people bothering the bread – squeezing it and squashed it and ripping open on the shelves, as well as loaves that are tossed having passed their sell-by date.

But there’s also a huge issue with supermarkets baking too much bread in store – Corin Bell who runs The Real Junk Food Project in Manchester suggests that supermarkets use hot, fresh bread as a marketing tool, knowing they can’t sell everything they bake.

How about baking bread at home - does that reduce its carbon footprint?

This is a pretty difficult question to answer, and depends on how you make your bread, but the short answer is: it doesn’t make that much difference.

A bread maker is the most efficient way, using about 0.5kWh per loaf compared to a supermarket bread oven using about 1kWh per loaf and a home gas oven using 1.5kWh per loaf.

If you do use your oven for baking then baking several loaves at once (and freezing a couple) is much more efficient than doing them one at a time.

Baking bread at home cuts out some of the emissions associated with transport and retail, and gives you more control over the flour that you use too.

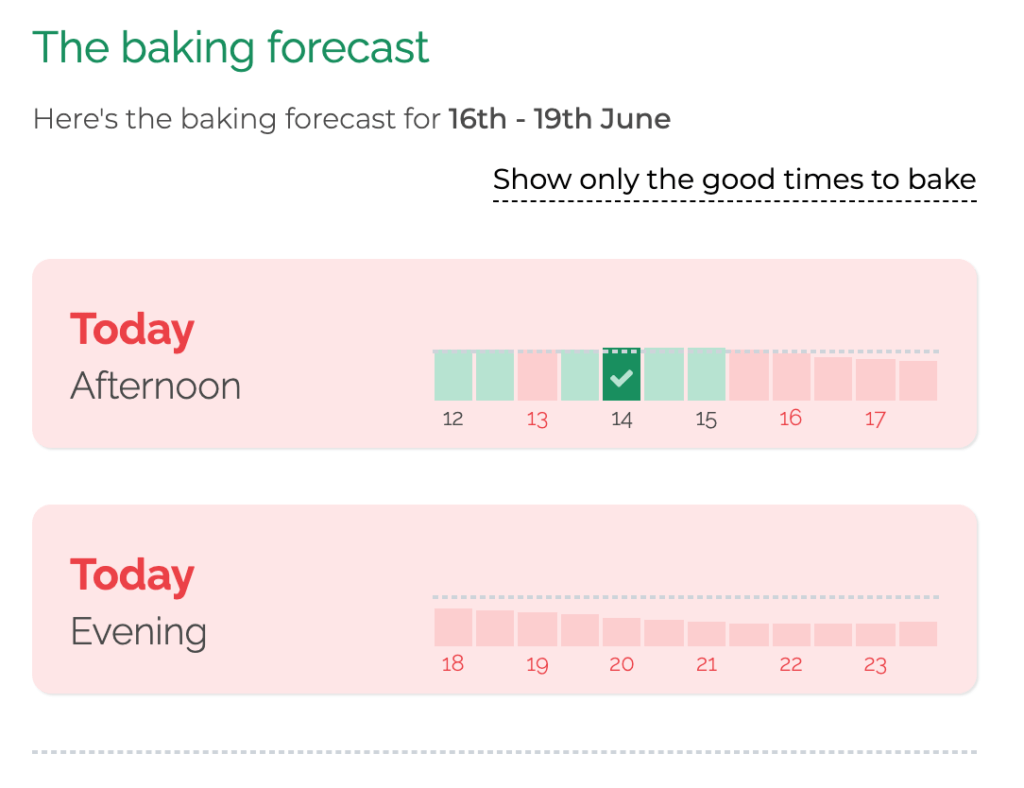

Introducing: The Baking Forecast

A great tool for home bakers is The Baking Forecast at shouldibake.com – this clever site recommends times for baking (or plugging in a bread maker) when more than a third of Britain’s electricity is coming from wind, solar and hydro power. As I write this, only 34% of our electricity is coming from renewables, but if I wait until 3:30 this afternoon then this will have gone up to 45%.

How does choosing organic bread or flour change things?

Organic farms tend to avoid synthetic fertilisers, which reduces one part of their carbon footprint, and less nitrogen leaching into soil and water systems takes the pressure off plants and wildlife. Using crop rotation, compost and manures, and growing plants that act as ‘green manures’ helps protect the soil from erosion and increases the amount of carbon the soil can store.

So that’s all good – however the question of whether organic farming is lower carbon overall is complicated, and contentious. As organic farming is (currently) lower yielding, more land is needed to feed the same number of people, and some studies have shown that organic farming releases as much, or possibly even more, of that potent warming gas nitrogen. Other researchers disagree, saying most studies don’t fully take the reduction in fertiliser use into account.

The conclusion? If organic works with your budget, choose it over non-organic, but cutting out waste is still going to be the most meaningful thing you can do.

Ok, fine – so what can I do right now?

I’m so glad you asked, because reducing our bread emissions is a piece of toast.

In terms of carbon footprint, the bread we buy, the type of loaf and the packaging do all make a small difference, with thick sliced wholemeal bread in a plastic bag coming out on top. This is because the wholemeal uses the grain more efficiently, the thick slices reduce our toaster use (as there are fewer of them in the loaf) and the plastic bag produces less methane than a paper bag when it ends up in landfill. Obviously eating all our bread untoasted and recycling/ composting a paper bag – or even buying bread naked and taking a tote – would reduce its footprint further.

Tweaking our bread habits

Whatever bread we make or buy, there are some simple things we can do to make it stay fresher for longer, meaning we’re more likely to eat it!

- Keep shop bought bread in its bag, and keep it somewhere dark, not out on the surface.

- Clean your bread bin out weekly (I am terrible at doing this) as mould spores can lurk in there, turning your bread furry fast.

- If you’re baking bread, wait until it’s cool to cut it, then store it cut side down. If you find it’s getting too dry, wrap it in a cotton bag, beeswax wrap, or plastic bag.

- If your loaf gets a bit stale, slice it and sprinkle the slices with water then pop it in the over for 5 minutes (ideally when the oven is already hot from cooking something else).

- If you’re baking, only pre-heat the oven just before you need it, and – if it’s a cold day – leave the oven door open after baking to warm up the kitchen.

Love on your crusts

1.29 billion crusts get chucked every year – that’s £62 million of decent bread. I think crusts need some re-branding in the Green Squirrel household as we call it ‘the knob end’ and I don’t know if that’s really selling it, but we do have a couple of favourite ways to use them up…

- Freeze them and make a batch of breadcrumbs. Just chuck them in a freezer bag and, once the bag is full, get them out to defrost and let them sit uncovered for a day or so to get stale (or put them in the oven to dry in the residual heat after you’ve finished cooking something else). Blitz them in a food processor or grate them with the cheese grater. We love to make Pangrattato – also known as Poor Man’s Parmensan – to top pasta, salads, and soups.

- Make a ooey-gooey bread and butter pudding. Here’s a sweet option and here’s a savoury one.

Look out for more bread-based recipes in the Cooking and Eating space this week, and do pop in and share your own.

What do you call it?

In some very important, serious, and definitely climate-related research I discovered that some common regional names for the bits at either end of a loaf include…

The knobby

The doormat

The heel

The bum

The topper

The bumper

The Norbert.

…Norbet?!

What can I do next?

If you’re looking to take the next step, you could do worse than making your own sandwiches (rather than buying lunch out) and experimenting with some low carbon toast toppings and sandwich fillings, as the stuff we pair with bread is likely to have a much greater footprint than the bread itself.

Researchers at the University of Manchester studied the forty most popular sandwich fillings in the UK (in case you’re curious, chicken salad came out on top, shortly followed by prawn mayo) to rank their climate impact. Egg and cress, the least popular sandwich filling, actually came out on top in terms of emissions, clocking in at 739g CO2e compared to a meaty breakfast sandwich at 1141g CO2e (more than an entire loaf of bread!).

DIYing your lunchbox sarnies has a big impact, with shop-bought ham, cheese, mayo sandwich have a footprint 2.2 times greater than a homemade version with the same ingredients. Switching out high-carbon fillings will make an even greater difference – here are a few ideas:

🥪 Coronation chickpeas – I love this, it makes a great salad or sandwich filling and it’s lovely stuffed in a pitta.

🥙 Falafel, spring onions, lettuce and chilli sauce.

🍏Marmite, cream cheese (vegan or dairy) and apple slices.

🥬 Pickled beetroot, hummus, lettuce.

🌶️ Onion bhajis (buy a pack for the freezer or make your own and freeze), plain yoghurt, cucumber, mint (and maybe some spicy chutney).

🍅 Roasted veg and sundried tomatoes

🥄Scrambled tofu (better in a pitta, it all tumbles out of a sandwich!)

What’s your favourite sandwich filling? Bonus points if it’s a bit weird – come over to the Community Space and let us know, and find out what my guilty pleasure sandwich is…

I’m obsessed with this – how do I go further?

You could find out whether there’s a Community Supported Bakery – bread made by local people for local people – in your area. If you’re interested in setting one up then the Real Bread Campaign have produced a free downloadable book – Knead to Know – to take you through the steps.

You could also have a go at making your own beer from bread scraps – Toast Ale, who have so far saved 42 tonnes of CO2 by making craft beer from commercial bread waste, have shared their recipe so you can have a go too.

Read more

A field of wheat. This project brought together 42 members of the public, artists, and businesses to collaborate on the management of a wheat field over an entire year – it’s fascinating.

The Real Bread Campaign promotes bread that is better for people and planet.

Ammonium nitrate, the forgotten element of climate change.

The Heritage Grain Trust is a non-profit with the aim of developing a new approach to growing grain for human consumption, one that encourages resilience in the face of climate change and reduces the loss of biodiversity

References

The environmental impact of fertilizer embodied in a wheat-to-bread supply chain.

The greenhouse gas impacts of converting food production in England and Wales to organic methods.

Towards better representation of organic agriculture in life cycle assessment

Greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram of food.